Deep Dive

| Wheelies | Interlude | Deep Dive | From Wheelies, Arabesques |

| From Arabesques, Wheelies | Wheelie Animations |

Draw an arabesque from a chain of wheelies. Figures 3 through 5 shows how it goes. The first plays a single wheelie and begets the simplest of arabesques. The second — a chord of two spinning wheelies — plays a more involved fioritura. The third lets fly with a three-way fandango. Up to now, that's always been our play: link ever more lengthly wheelie chains to draw ever more labyrinthine arabesques.

But what is beneath this pursuit? Can we devise a math for such pile-ons? Given wheelies, can we derive the arabesque? And, from the arabesque, might we also lay bare wheelies?

| 6. Arabesques and Sinusoids |

We start with the math. An arabesque at its simplest is no more than an origin-centered wheelie — a circle — plotted over time on the complex plane; see Figure 6. It orients along the real axis and rotates counterclockwise at one cycle per period, aka, a "Hertz". "Period" is relative time; it proxies for what could be a microsecond or millenia — and who cares? It's the drawing, not the duration of its drafting, that matters.

The complex plane offers the plan view (upper right). Changing over to the elevations sets apart wheelies into real and imaginary components: a pair of sinusoids. One elevation, cos(2πft + θ), constructs a real axis oscillation at frequency f, while its phase-shifted counterpart, i cos(2πft + θ + π/2) ⇒ i sin(2πft + θ) constructs a similar imaginary axis oscillation. The quarter-period phase shift between the two produces a circular wheelie orbiting in the complex plane with the passage of t.

![\begin{matrix} \psi (t) = r(\cos {(2\pi f t + \theta)} + i\sin {(2\pi f t + \theta)}) & t \in [0,\dots ,1] & \textsf{E. 1} \end{matrix}](img/_begin_matrix_psi_t_r_cos_2_pi_f_t_theta_i_sin_2_pi_f_t_theta_t_in_0_dots_1_textsf_E_1_end_matrix_.png)

And that's the math. Sinusoids conjure the wheelie; a point traversing the wheelie conjures the sinusoids. They are cognates, in that sinusoids oscillating through time and wheelies rotating on planes are each, in their own guises, Lego® blocks.

A wheelie encapsulates:

| 1. | a single frequency ( f ), |

| 2. | its sign ( ± ) — that is, its clockwise ( – ) or counterclockwise ( + ) handedness, |

| 3. | an initial angular offset ( θ ) and |

| 4. | magnitude ( r ). |

Musicians call such primitives partials — essential harmonic building blocks. Combine partials to make pleasant sounds. Combine wheelies to make pleasant arabesques. It is all the same math.

There is an apt — though perplexing — alternative to Equation 1 that facilitates wheelie combinations. Around 1740, Leonhard Euler laid bare an exponential form:

![\begin{matrix} \psi (t) = re^{i(2\pi f t + \theta)} = r(\cos ({2\pi f t + \theta}) + i\sin ({2\pi f t + \theta})) & t \in [0,\dots ,1] & \textsf{E. 2} \end{matrix}](img/_begin_matrix_psi_t_re_i_2_pi_f_t_theta_r_cos_2_pi_f_t_theta_i_sin_2_pi_f_t_theta_t_in_0_dots_1_textsf_E_2_end_matrix_.png)

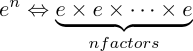

Here's the perplexing bit: Old-school pupils of elementary exponentiation perceive:

as the base value e “multiplying” itself n times. In this light, Equation 2 poses mysteries. Multiply e by itself an — imaginary — number of times (that's what i means!!!)??? So, how do “imaginary” repetitions differ from real ones?

The mind boggles.

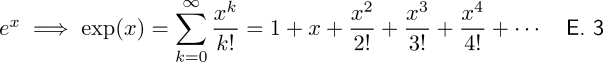

To get over that, know that mathematical notation sometimes borrows carelessly from itself. The borrowed notation here is exponentiation, and its borrowing obscures an operation with a broader remit, the exponential function:

Rather than indicate the times one multiplies a base, e, by x — what Equation 3's left-most side purports — the "exponent" x should be taken as an argument of the exponential function. That is, it is more like the "function call" notation of the second representation. Take the "exponent" as an argument, mentally wrap it in parentheses and, on the right hand side, substitute x with the parenthetically wrapped argument. Structurally x may take many forms: integer, real, complex, quaternion — x is an argument parameter, not a repetition count.

And what is the right hand side? It is the Taylor Series expansion of exp(x). Its utility lies in its polynomial representation, which is readily amenable to integration and differentiation. Differentiation is especially magical. Should we differentiate the right hand polynomial term by term:

![\begin{array}{ccc} \textit{x} & \implies & \textit{dx} \\ \hline 1 & \implies & 0 \\ x & \implies & 1 \\[0.5em] \frac{x^2}{2} & \implies & x \\[0.5em] \frac{x^3}{6} & \implies & \frac{x^2}{2} \\[0.5em] \frac{x^4}{24} & \implies & \frac{x^3}{6} \\[0.5em] \frac{x^5}{120} & \implies & \frac{x^4}{24} \\[0.5em] \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \end{array}](img/_begin_array_ccc_textit_x_implies_textit_dx_hline_1_implies_0_x_implies_1_0_5em_frac_x_2_2_implies_x_0_5em_frac_x_3_6_implies_frac_x_2_2_0_5em_frac_x_4_24_implies_frac_x_3_6_0_5em_frac_x_5_120_imp.png)

First, one does not need to work through very many terms before glancing diagonally — and down — and recognizing that these differentiations are, in fact, reproducing the same series — that the exponential function in x is its own first derivative. And, by extension, its own second derivative, and its own third derivative… et sic porro. Consequently, the exponential function crops up in self-referential realms where the rate of change of a value is proportional to the value itself: realms such as exponential growth, radioactive decay and compounding interest.

Second, substituting 0 for x — that is, evaluating e⁰ — finds the entire Taylor series vanishing after the constant term 1. Alas! e⁰ ⇒ 1! A something-from-nothing biennale that leaves the old-schooled astonished: how is it now that something that is not even multiplied by itself — just once! — can ever be anything at all?

Third, scaling this function's argument by a constant, a, we have:

![\begin{array}{l} \frac{d}{dt}e^{ax} = ae^{ax} \\[0.5em] \end{array}](img/_begin_array_l_frac_d_dt_e_ax_ae_ax_0_5em_end_array_.png)

The derivative of an exponential function with a scaled argument is just the function itself, now similarly scaled.

Finally, what does:

Start with the Taylor series expansion. Evaluating exp(iθ) through Equation 3, we uncover similar Taylor expansions for the cosine and sine functions. By substitution, we again have the identity that Euler uncovered some two hundred eighty years ago:

![\begin{array}{ll} e^{i \theta} = \exp(i \theta) = &1 + i \theta + \frac{i^2 \theta^2}{2!} + \frac{i^3 \theta^3}{3!} + \frac{i^4 \theta^4}{4!} + \cdots \\[0.5em] &\left( 1-\frac{\theta^2}{2!}+\frac{\theta^4}{4!}-\frac{\theta^6}{6!}+\cdots \right) + i\left(\theta - \frac{\theta^3}{3!} + \frac{\theta^5}{5!} - \frac{\theta^7}{7!}+\cdots\right) \\[0.5em] &\cos (\theta) + i\sin (\theta) \end{array}](img/_begin_array_ll_e_i_theta_exp_i_theta_1_i_theta_frac_i_2_theta_2_2_frac_i_3_theta_3_3_frac_i_4_theta_4_4_cdots_0_5em_left_1_frac_theta_2_2_frac_theta_4_4_frac_theta_6_6_cdots_right_i_left_theta_fr.png)

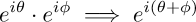

That is, exp(iθ) looks like a unit vector that has been rotated counterclockwise from the x axis by angle θ, leaving projections cos(θ) on the real axis and i·sin(θ) on the imaginary axes. Additionally, through the law of exponents, expressions:

Thus, notational discomposures aside, expressions like:

are not so much Old School power raising as they are origin-rooted vectors with a length r, sweeping out counterclockwise 2π radian angles at rotational frequencies of f over periods of t: the quintessential wheelie.

Likewise, if over time the position, d(t), of a complex plane point is governed by d(t) = r·exp(it), such as with the tip of a rotating wheelie, then its velocity over time is its first derivative:

| Previous: | Wheelies | Next: | From Wheelies, Arabesques |

Updated: Sun 22-January-2023 22:22:58 UTC Commit: 846e5989e3a4

Home

Home Download

Download News

News Mastodon

Mastodon Bluesky

Bluesky X

X Summary - 17 Years

Summary - 17 Years Summary - 16 Years

Summary - 16 Years Summary - 15 Years

Summary - 15 Years Summary - 13 Years

Summary - 13 Years Summary - 11 Years

Summary - 11 Years Summary - 10 Years

Summary - 10 Years Resources

Resources Technical Reference

Technical Reference Scripting Tutorial

Scripting Tutorial Video Tutorials

Video Tutorials Wiki Pages

Wiki Pages Image Gallery

Image Gallery Color Presets

Color Presets Using libgmic

Using libgmic G'MIC Online

G'MIC Online Community

Community Discussion Forum (Pixls.us)

Discussion Forum (Pixls.us) GimpChat

GimpChat IRC

IRC Report Issue

Report Issue