Cauldron, Anyone?

The G'MIC image has three spatial dimensions; it is mostly out of habit and custom that many people (this writer included) generally fuhgeddaboudit and only use single-slice, two dimensional images. That is a shame, as many G'MIC commands do their bidding in three dimensions as well as two. They are untapped sources of cheap (in terms of rendering time) animation.

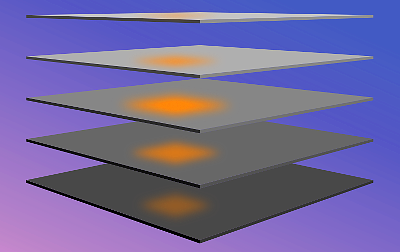

The G'MIC image has three spatial dimensions; it is mostly out of habit and custom that many people (this writer included) generally fuhgeddaboudit and only use single-slice, two dimensional images. That is a shame, as many G'MIC commands do their bidding in three dimensions as well as two. They are untapped sources of cheap (in terms of rendering time) animation.The diagram on the left illustrates how the blur command behaves when an image has more than one slice. An orange pixel affects neighbors along the z axis (depth) as well as along the x and y axes. Play these slices as an animation and the blurred pixel becomes a kind of a pop! explosion.

The bandpass command also operates in three dimensions. In other places, we've harnessed this command for spectral filtering, eliding all but a subset of frequencies in the original image. Taking an image with such truncated spectral content back into spatial domain gives rise to a set of sine waves that do not quite reconstitute the original; we see patterns of constructive reinforcement and destructive interference that would not have been especially noticable had we not erased those parts of the spectrum needed to reconstitute the original.

The key idea in this Cookbook piece is this: bandpass, like many G'MIC commands work in three dimensions. And when we think Animation, that extra dimension can be time. The following example happens to use the -bandpass command, but the techniques presented here aren't married to that command. They can be generalized to any other command which operates in the round over slices as well as the width and height of images.

Pipeline

Here is a pipeline that produces a kind of a cauldron effect. The nice thing about clips produced by this pipeline is that they can be seamlessly looped without a pop crossing from the end to the beginning of the loop. Details follow.cauldron:

-input 360,240,200,3

-noise[-1] 0.2,2

-bandpass 2%,3%

-normalize 0,255

-display

-split z

-output cauldron.mp4,24,h264

$ gmic cauldron.gmic -verbose + -cauldron -verbose -

[gmic]-0./ Start G'MIC interpreter.

[gmic]-0./ Input custom command file 'cauldron.gmic' (1 new, total: 4552).

[gmic]-0./ Increment verbosity level (set to 2).

[gmic]-0./cauldron/ Input black image at position 0 (1 image 360x240x200x3).

[gmic]-1./cauldron/ Add salt&pepper noise to image [0], with standard deviation 0.2.

[gmic]-1./cauldron/ Apply bandpass filter [2%,3%] to image [0].

[gmic]-1./cauldron/ Normalize image [0] in range [0,255], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-1./cauldron/ Display image [0] = '[unnamed]', from point (180,120,100).

[0] = '[unnamed]':

size = (360,240,200,3) [197 Mio of float32].

data = (128.162,131.093,133.638,135.768,137.465,138.717,139.523,139.89,139.832,139.374,138.546,137.386,(...),127.24,126.957,126.86,126.962,127.271,127.793,128.532,129.489,130.661,132.043,133.626,135.401).

min = 0, max = 255, mean = 129.187, std = 28.3084, coords_min = (344,103,28,0), coords_max = (38,157,34,0).

[gmic]-1./cauldron/ Split image [0] along the 'z'-axis.

[gmic]-200./cauldron/ Output images [0,1,2,(...),197,198,199] as mp4 file 'cauldron.mp4', with 24 fps and h264 codec.

[gmic]-200./ Decrement verbosity level (set to 1).

[gmic]-200./ End G'MIC interpreter.

-input 360,240,200,3

-noise[-1] 0.2,2

-bandpass 2%,3%

-normalize 0,255

-display

-split z

-output cauldron.mp4,24,h264

$ gmic cauldron.gmic -verbose + -cauldron -verbose -

[gmic]-0./ Start G'MIC interpreter.

[gmic]-0./ Input custom command file 'cauldron.gmic' (1 new, total: 4552).

[gmic]-0./ Increment verbosity level (set to 2).

[gmic]-0./cauldron/ Input black image at position 0 (1 image 360x240x200x3).

[gmic]-1./cauldron/ Add salt&pepper noise to image [0], with standard deviation 0.2.

[gmic]-1./cauldron/ Apply bandpass filter [2%,3%] to image [0].

[gmic]-1./cauldron/ Normalize image [0] in range [0,255], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-1./cauldron/ Display image [0] = '[unnamed]', from point (180,120,100).

[0] = '[unnamed]':

size = (360,240,200,3) [197 Mio of float32].

data = (128.162,131.093,133.638,135.768,137.465,138.717,139.523,139.89,139.832,139.374,138.546,137.386,(...),127.24,126.957,126.86,126.962,127.271,127.793,128.532,129.489,130.661,132.043,133.626,135.401).

min = 0, max = 255, mean = 129.187, std = 28.3084, coords_min = (344,103,28,0), coords_max = (38,157,34,0).

[gmic]-1./cauldron/ Split image [0] along the 'z'-axis.

[gmic]-200./cauldron/ Output images [0,1,2,(...),197,198,199] as mp4 file 'cauldron.mp4', with 24 fps and h264 codec.

[gmic]-200./ Decrement verbosity level (set to 1).

[gmic]-200./ End G'MIC interpreter.

| 1. | First, we conjure from the aether a contiguous volume 320 pixels wide, 240 pixels high and two hundred slices deep, sufficient for an eight second video clip playing at 24 frames per second. Into this conjured image, we salt-and-pepper a fairly sparse pattern of pixels. If you scrub through the image volume at this point in the pipeline (insert display after noise), the animation would have the appearance of dirty film. To this sparse noise we apply a low-pass spectral filter, using the bandpass command. The lower relative cutoff frequency is 2%, the upper relative cutoff frequency is 3%. That is, of 100% of the original image spectra, we toss all frequencies but a one percent wide band between the 2%-3% markers. |

| 2. | Behind the scenes, the bandpass command harnesses the Fast Fourier Transform, embodied in the fft command, converting the three dimensional array of pixels into a similar array of spectral coefficients, this through a process of Fourier analysis. It then deletes all but a hollow sphere of coefficients around the spectral space origin. The lower and upper relative cutoff frequencies set the thickness of this shell and establish the overall character of the animation. By cutoff, we mean that we set coefficients beyond these limits to zero and preserve coefficients within. |

| 3. | Here, we picked low relative frequencies, producing only very large features that seem quite blurry, characteristics of a low pass frequency filter. Larger relative frequencies would give rise to high-pass filters, admitting smaller, sharper features, while the difference between the numbers controls the amount of variation in feature size. Experimenting with these numbers can give rise to a great deal of variety in texture and variation. The noise command also affects the texture of the pattern, particularly for larger values of cutoff frequencies. |

| 4. | With a much-elided set of spectral coefficients, the bandpass command invokes the ifft command, partially reconstituting the spatial image through the inverse process of Fourier synthesis. |

| 5. | At the end of the command pipeline, housekeeping prevails. The reconstituted image generally will not be in a range suitable for presentation display; normalize shifts all intensities into the 0,255 range, a suitable width for eight bit color animation. We use the split command in preparation for output, a command which can create a video, but which needs a sequence of one slice images. By way of particular file extensions, one may specify one of five multimedia containers: Quicktime (.mov), Motion Picture Expert Group (MPEG) (.mp4), Flash (.flv), Ogg/Vorbis (.ogg) or Audio Video Interleaved (.avi). This pipeline harnesses the MPEG container (.mp4 file extension). The ",24" notation attached to the file extension sets the 24 frame-per-second rate for the stream. |

| 6. | The multimedia file produced by the output command contains an h264 video stream in an MPEG container, which can be played on a wide range of hardware. If you need to tailor the multimedia stream in more precise ways, save the stream as an image sequence. Choose a lossless image file format like Portable Network Graphic images (.png). The resulting sequence of numbered files may be then imported into Blender's video editor and combined with other media. |

The Cauldron, sans title. See Further Explorations for titling this animation.

The video clip above is a product of the previous G'MIC command pipeline. It reminds us of percolating liquid in a cauldron. Poetic interpretations aside, we are observing the low frequency components of sparsely scattered noise, a three dimensional interference pattern which our "camera" depicts two dimensionally, displaying slices through time. Particular curdling textures depend very much on the choice of the lower and upper relative cutoff frequencies that we gave to the -bandpass command. Larger relative frequencies give rise to finer, higher frequency detail. The blobs are smaller and seem to curdle faster. A larger difference between relative frequencies admits a wider range of blob sizes. The cutoff frequencies can be set too close together. If the difference between the lower and upper relative frequencies becomes too small, the resulting images may be all black.

Because this sequence is a product of Fourier analysis and synthesis, it can be seamlessly tiled in the x, y, and z dimensions. Not only do the top and bottom and left and right edges match, but the end of the animation segues into the beginning, so this material can be used out of the box in an endless loop without having to worry about a pop as the animation loops around. This characteristic stems entirely from the -bandpass command and the underlying Fourier transform commands, fft and ifft.

Further Explorations

Nearly everything we do with G'MIC is not an end in itself, but furnishes stepping stones to other effects. The cauldron animation can furnish displacement fields to distort other visuals, and the cauldron visual need not even appear itself.

The Title, sans Cauldron.

This is a title image made by Inkscape and then exported as a PNG file. We matched its aspect ratio to the cauldron clip shown in the previous section, 360x240 pixels. Our aim is to composite this title with the cauldron clip, so we have included an alpha channel in the image file. In this manner, the base video will be visible through the transparent regions of this title image.

To distort this title, as if it being affected by the cauldron, we will harness G'MIC's warp command. -warp uses channel zero to shift a target image along the horizontal axis and channel one to shift along the vertical axis. We'll extract these channels from each frame of the caudron clip and apply them to the title image. Since it would be tedious to do this manually for each of the 200 frames in the cauldron clip, we will avail ourselves of a G'MIC loop commands, repeat <n>... done.

The Cauldron, with a turbulence Stirred title.

cauldron_over:

-input cauldron.mp4

-blur 1

-input cauldron_title.png

-repeat $!-1

-local[$>,-1]

+channels[0] 0,1

-normalize. -15,15

+warp[1] [-1],1

-remove..

-shared. 100%

-normalize. 0,255

-remove.

-blend[0,-1] alpha

-done

-done

-remove.

-output cauldron2.mp4,24,h264

$ gmic cauldron_over.gmic -cauldron_over

[gmic]-0./ Start G'MIC interpreter.

[gmic]-0./ Input custom command file 'cauldron_over.gmic' (1 new, total: 4552).

[gmic]-200./ End G'MIC interpreter.

-input cauldron.mp4

-blur 1

-input cauldron_title.png

-repeat $!-1

-local[$>,-1]

+channels[0] 0,1

-normalize. -15,15

+warp[1] [-1],1

-remove..

-shared. 100%

-normalize. 0,255

-remove.

-blend[0,-1] alpha

-done

-done

-remove.

-output cauldron2.mp4,24,h264

$ gmic cauldron_over.gmic -cauldron_over

[gmic]-0./ Start G'MIC interpreter.

[gmic]-0./ Input custom command file 'cauldron_over.gmic' (1 new, total: 4552).

[gmic]-200./ End G'MIC interpreter.

Distorted Title Walkthrough

| Image List | Notes |

| Step 0: When G'MIC loads a video file, it automatically converts the frames to sRGB, a colorspace which can be read by most paint programs, and separates the frames out as separate images. The blur step is optional; it smooths out any minor artifacts introduced by the creation of the video. As a consequence, there are hundreds of items on the image list. To this we add the title slide. |

| Step 1: repeat and local, together with their companion -done and -done, create an image list iterator. See the -repeat...-done and -local...-done tutorials. In effect, these paired sets of commands successively take up one frame from the video along with the undistorted title slide. The indented commands between the -local...-done pairs have a private image list, distinct and separate from the outer image list. During each iteration, these commands constituting the inner -local...-done environment distort the title slide in a manner controlled by the cauldron pattern from the video frame. It then composites the distorted title with the cauldron frame. The iteration repeats until all frames have been "stamped" with the cauldron title, distorted in a way controled by the cauldron pattern. Details follow. |

| Step 2: At the outset of each iteration, only two images make up the private image list: one frame from the video and the title slide. channels operates on the video frame. It extracts the red and green channels of the frame into a separate image, the third on the private list, creating a distortion field for use by the warp command. The warp tutorial goes into detail on how distortion fields work. Here, the specific red and green channels taken from the video frame determine how the letterforms bend. Normalizing the distortion field between ± values controls the magnitude of the distortion. Here, ± 15 means that title slide pixels will, at most move fifteen pixels in the horizontal and vertical directions. |

| Step 3: The warp command harnesses the distortion field to distort the title slide. After it's use, we drop the distortion field from the image list by the remove command. It is no longer needed; we will create a new distortion field based on the next video frame during the next iteration. |

| Step 4: The next couple of steps are optional, born of a sense of prudence. We re-normalize the transparency channel of the distorted title slide, as warp can alter pixel values. As a precaution, we renormalize them to the 0-255 range. The means by which we do this is common: The shared command allows us to access internal components of an image and operate on it as if it is a separate image on the list. See the share tutorial for more information. In this example, we renormalize the alpha channel quickly because we are operating on the channel without needing to copy it out of the image, and then re-copy it back into the image. |

| Step 5: The blend command is G'MIC's general compositing tool. The alpha blend composites the distorted title onto the frame. And... we are done with one frame. On the next iteration, we take up the next frame on the outer image list, pulling it onto the inner list for the next round. |

| Step 6: done executes when all images on the list have been processed. We remove the undistorted title slide leaving only the now-title-stamped frames. We write out the video in the same manner as we did initially with the cauldron effect. |

Home

Home Download

Download News

News Mastodon

Mastodon Bluesky

Bluesky X

X Summary - 17 Years

Summary - 17 Years Summary - 16 Years

Summary - 16 Years Summary - 15 Years

Summary - 15 Years Summary - 13 Years

Summary - 13 Years Summary - 11 Years

Summary - 11 Years Summary - 10 Years

Summary - 10 Years Resources

Resources Technical Reference

Technical Reference Scripting Tutorial

Scripting Tutorial Video Tutorials

Video Tutorials Wiki Pages

Wiki Pages Image Gallery

Image Gallery Color Presets

Color Presets Using libgmic

Using libgmic G'MIC Online

G'MIC Online Community

Community Discussion Forum (Pixls.us)

Discussion Forum (Pixls.us) GimpChat

GimpChat IRC

IRC Report Issue

Report Issue