Eigen Thingys

Tensors have gotten bandied about a lot in these Recipes. But what are they?They are, among other things, matrices, and, among other things matrices are linear maps that tell us what size and in which direction vectors will point after we have taken them from from a space we know about to a space we care about.4 Here, “take” is shorthand for “the matrix product of linear map A and column vector _v_”

That is, v' usually points somewhere other than v, and has a different size or magnitude, because of its matrix multiplication by tensor A, a linear map. A takes v from the space we know about to a space we care about, where v suddenly looks like v'. For example, if v is ten meters long and points towards zero degrees azimuth (0°) in the space we know about, then A makes a new vector, v' which is three meters long and points towards 192° azimuth in the space we care about.

| 1. | Spock: “Captain. Proceeding at Warp Factor 10 at zero degrees.” 10.0 ∡ 0.0° → left [ matrix{ 10.0 ## 0.0 } right ] |

| 2. | left [ matrix{ -0.29344428 # 0.06237351 ## -0.06237351 # -0.29344428} right ] left [ matrix{10.00 ## 0.00} right ] = left [ matrix{ -2.9344428 ## -0.62373507 }right ] |

| 3. | left [ matrix{ -2.9344428 ## -0.62373507 }right ] = sqrt{-2.9344428^2 + -0.62373507^2} ∡ arctan(-0.62373507, -2.9344428) |

| 4. | Spock: “Captain: Now proceeding at Warp Factor 3 at 192 degrees.” 3.00 ∡ 192.0° |

Often the space we know about and the space we care about is one and the same, so we call the linear map an operator. The salient aspect of this operator is that nearly every vector filtering through it will change length and direction.

If we make a study of this, however, we will discover that some vectors for some operators do not undergo a change in orientation. If there is any change in direction at all, it is a simple reversal, as if we had picked up the vector and turned it front-to-back so that it is still parallel with its old direction, and not lying transverse to it in any way. At most, whatever happens to this particular class of vectors is a change of size, and we can interpret a simple reversal of direction as a “negative” change of size.

| 1. | Linear Map B: left [ matrix{ 0.78 # 0.55 ## 0.55 # 1.32 }right] |

| 2. | vector u: 1.0 ∡ 148.0734° = left [ matrix{ -0.84873 ## 0.52883} right ] ; vector v: 1.0 ∡ 238.0734° = left [ matrix{ -0.52883 ## -0.84873 } right ] |

| 3. | {bold B}u = left [ matrix{ 0.78 # 0.55 ## 0.55 # 1.32 }right]left [ matrix{ -0.84873 ## 0.52883} right ] = left [ matrix{ -0.37115 ## 0.23126} right ] = 0.4373 times left [ matrix{ -0.84873 ## 0.52883} right ] = 0.4373 ∡ 148.0734° |

| 4. | {bold B}v = left [ matrix{ 0.78 # 0.55 ## 0.55 # 1.32 }right] left [ matrix{ -0.52883 ## -0.84873 } right ] = left [ matrix{ -0.87929 ## -1.41118 } right ] = 1.6627 times left [ matrix{ -0.52883 ## -0.84873} right ] = 1.6627 ∡ 238.0734° |

Here, vectors u and v did not change orientation. The linear map B simply rescaled them. We call such vectors “eigenvectors” for linear map B, and the rescaling factors its “eigenvalues”. Here's a matrix equation describing the phenomenon:

In this relation, the vector which merely undergoes a change in scale is the eigenvector, v, and the scaling factor is the eigenvalue, λ.

That's the essence of eigenvectors and eigenvalues. Notice that we associate these objects with linear map B. Those familiar with German probably recognize that the prefix eigen roughly means "self-" or "unique to" or "peculiar to". Eigenvectors and eigenvalues are tightly coupled to the tensor from which they arise. Indeed, they reveal a significant characteristic of the tensor. Here are some illustrations.

| 1. | Merry-go-rounds turn people round-and-round, except in one direction, the pole around which the merry-go-round turns. That pole contains eigenvectors. Allied with the infinite number of rotation tensors that encode the various degrees of merry-go-rounding, there are eigenvectors aligned with the pole which do not change direction as the merry-goes-round. Should we happen to know about the direction in which the eigenvectors point, we have identified the axis around which the merry-go-round turns. |

| 2. | We've drawn a square on a perfectly rubbery piece of paper. We grab the left and right edges of the paper, pulling the right edge up as we pull the left edge down. The square devolves into a general parallelogram with corners no longer at right angles. There is a tensor A, to which we can report position vectors of old points on the square and it will tell us their new positions on the parallelogram. This tensor also tells us that two points are in exactly the same position as before. The position vectors of these remarkable points are oriented straight up and straight down. These are the eigenvectors of the shear tensor A and we know from their orientation what the axis of the shear is. |

G'MIC Structure and Diffusion Tensors

The big problem, of course, is how computers can see anything without eyeballs. We want G'MIC to make our pictures less noisy, but please don't mess up the edges. OK, then, how is G'MIC supposed to find the edges when it lacks eyeballs? It is a good question, really, and it keeps computer vision researchers employed when they'd be otherwise robbing gas stations.Lacking eyeballs, G'MIC makes do with tensors.

For G'MIC to smooth around edges, but without smoothing the edges themselves, it first has to know where the edges are. The particular command which tells G'MIC about edges is structuretensors. This command computes, for a 1024 × 1024 pixel image, exactly 1,048,576 structure tensors, one for each pixel in the image.

At first, structuretensors has no idea what any of these tensors are, but it knows what it wants.

Consider the two dimensional case. For each pixel, structuretensors wants a local map, a tensor, with one eigenvector that points along the orientation of a local contour or edge (if there is one), and another, right angles to the first, that points along the slope of the most rapid intensity change – the gradient – (if there is one).

Call the first vector the contour vector and the second the gradient vector; structuretensors also wants the tensor's eigenvalues. If the eigenvalue of the contour vector is zero (or very nearly so), while the one for the gradient vector is large, then the command has found that holy of holies, an edge signal, which, for a computer sans eyeballs and feeling its way through an image, is as good as a pair of eyes (or nearly so). Eigenvalues which differ greatly in magnitude is said to have a high measure of anisotropy and signals an edge. It becomes structuretensors business to locate tensors with these kind of eigenvalues because to locate these is to find edges.

structuretensors finds these by visiting every pixel in the image. At each visit:

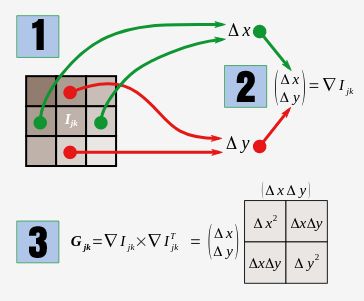

| 1. | the command measures the gradient differences along the principle axes of an image. These are the intensity differences along the width (Δx, green arrows) and height ( Δy, red arrows) of pixels immediately adjacent to the assay pixel, Ijk. |

| 2. | These differences may be regarded as a particular kind of vector called a del, (∇) marked by a nabla, a symbol looking more or less like an inverted triangle. The del captures the measurable horizontal and vertical change in intensity at pixel Ijk .which the command interprets as a vector. |

| 3. | The outer product of the del with its transpose is just the matrix product of its column and row forms, which produces a tensor product. In essence, the command arranges the del horizontally as column headers and vertically as row labels and computes coefficients from products of column and row pairings. The matrix arising from these computations is a structure tensor. |

Providentially, the structure tensor is just the matrix which G'MIC needs for eyeballs. It has one eigenvector that can align with the local gradient at Ijk, if one exists, and another which aligns with a local edge, again, if one exists.

The coherence cjk of the structure tensor at pixel Ijk tells us how “strong” this edge may be:

c_jk = left ( {%lambda_1 - %lambda_2} over {%lambda_1 + %lambda_2} right )^2

The strongest signal is one – one or another of the eigenvalues is zero and the value of the other is immaterial so long as it is positive. Zero signifies incoherence. That certainly is the case where Ijk is in a field of similarly luminous pixels. In that case, the local intensity differences are zero or nearly so, the del is a tiny or a zero vector, and the coefficients of the structure tensor are all zero or nearly so, ditto eigenvalues. The other circumstance is when both eigenvalues are about the same magnitude. Differences around pixel Ijk may very well be in abundance – but they do not cohere. Pixels in the midsts of noise gives rise to this condition.

The foregoing has dealt with single slice images, but the extension to images of greater depth is nearly identical. The structure tensor for images with a depth dimension is 3x3 to accommodate the additional difference calculation along the z axis, and, concomitantly, there are three eigenvectors and values instead of two. The logic of distinguishing edges from noise remains the same, however. Significant differences among any pair of eigenvalues indicates an edge in a width-, height-, or depth- trending direction.

In any case, the field which structuretensor produces constitutes a pattern of definite edges. structuretensors itself does not concern itself too much with the inventorying of edges. Its job concerns the calculation of tensor's coefficients from locally measured differences. For single slice images, structuretensors only has to store three values, as the structure tensor matrix is symmetric about the main diagonal and the two coefficients in the lower left and upper right cells always are equal.

structuretensors makes a three channel image of its operand, storing Δx2 in channel 0, ΔxΔy in channel 1 and Δy2 in channel 2. The display command assigns red, green, and blue to these channels. Structure tensors with vanishing coefficients appear gray in such images because the green channel can be negative. Potentially interesting pixels with non-zero structure tensors are colorful. Blue indicates horizontal edges while red signals the vertical. Northwest to southeast edges are a deep navy blue, almost black, while northeast to southwest edges are nearly white. Other orientations occupy tints and shades in between. Only humans appreciate the faux colors, though. G'MIC “sees” with structure tensors.

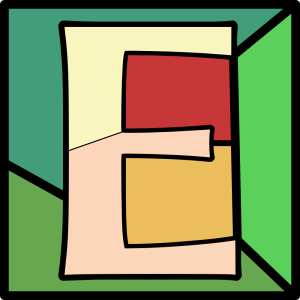

| A stained glass E with very distinct edges |

| A faux color display of the corresponding structure tensor field, produced by structuretensors. Gray corresponds with structure tensors with near-zero or zero coefficients. Red indicates structure tensors detecting vertical edges, blue corresponds to horizontal edges. A few diagonals appear, either as nearly white or navy blue. |

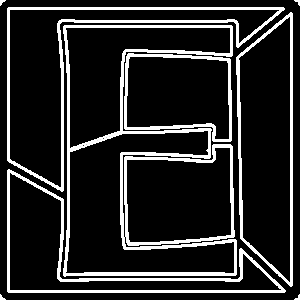

| White indicates pixels where coherence is exactly one, which identifies edges in the image. |

Notes

| 1. | Sadly, noise often makes this determination ambiguous. |

| 2. | peek at CImg.h and gmic_stdlib.gmic in your install directory |

| 3. | See convolve |

| 4. | The suspicious among you have registered the double use of “…among other things…” and, no doubt, suspect that the writer has left many things out, a crime to which the author readily pleads “Guilty.” Much as he's disposed to, he can't write an introduction to Linear Algebra here, but there are a couple of nice ones already written. First, there is Gerald Farin and Diane Hansford's Practical Linear Algebra: A Geometry Toolbox, written for the fellow who needs to understand the basic properties of linear algebra for computer graphics applications. On a more general level, there is Linear Algebra Done Right by Sheldon Axler, who has devised a gentle introduction to linear algebra without a premature introduction to determinants. If the first sentence of this page has left you faint at heart, it is best to skip it for now, but promise yourself some time with either of these books in the future. |

Home

Home Download

Download News

News Mastodon

Mastodon Bluesky

Bluesky X

X Summary - 17 Years

Summary - 17 Years Summary - 16 Years

Summary - 16 Years Summary - 15 Years

Summary - 15 Years Summary - 13 Years

Summary - 13 Years Summary - 11 Years

Summary - 11 Years Summary - 10 Years

Summary - 10 Years Resources

Resources Technical Reference

Technical Reference Scripting Tutorial

Scripting Tutorial Video Tutorials

Video Tutorials Wiki Pages

Wiki Pages Image Gallery

Image Gallery Color Presets

Color Presets Using libgmic

Using libgmic G'MIC Online

G'MIC Online Community

Community Discussion Forum (Pixls.us)

Discussion Forum (Pixls.us) GimpChat

GimpChat IRC

IRC Report Issue

Report Issue