shared

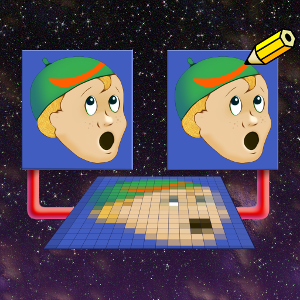

Extremely identical twins | shared places "clones" of its selected reference images on the stack. These clones — shared images — match almost every aspect of their referents — but are not copies. They share the image buffers of their referents instead of duplicating them. Any operation invoked on the share appears in the referent as well — and vice versa. Such sharing provides entry points to the referent's image buffer by way of the commands that operate on the shared image instead. One can limit the memory span of the shared region through different addessing schemes, limiting these to as small as a single pel in a particular row. Regardless, the shared region must be contiguous in the referent's image buffer. One cannot share rectangular or cuboid regions in a manner like a paint program selection. In laying out cuboid images onto linear memory buffers, such selections cleave image rows into left, center and right portions; row-on-row, the excluded left-and-rights interleave with the included centers, a noncontiguous disposition. |

The means of delimiting image buffers follow from how cuboid G'MIC Images lay out as nested fractions in a one dimensional linear image buffer. It is an arrangement of Matryoshka dolls with smaller fractions encompassed by larger. Contiguous runs of pels, the smallest fraction, form into rows, the next larger fraction and one spanning image width. In turn, Slices encompass contiguous sequences of rows, a larger fraction still, and spanning image width and height. Finally, channels subsume sequences of slices. This is the largest fraction, spanning image width, height and depth.

When delimiting a buffer so as to obtain a contiguous region, first decide what fraction serves your aims, then choose an argument variant graded in that fraction. shared supports argument variants for each fraction of interest and infers that fraction from the count of command arguments. The first two arguments establish a range of fractions; the remaining arguments provide coordinates that fix the range with respect to some row, slice or channel boundary:

| 1. | Three coordinates following a range fix a pel buffer (y, z, c) with respect to an antecedent row boundary. |

| 2. | Two coordinates following a range fix a row buffer, (z, c), with respect to an antecedent slice boundary. |

| 3. | One coordinate following a range fix a slice buffer, (c), with respect to an antecedent channel boundary. |

| 4. | Ranges suffice to fix channel buffers in the overall image: a two argument form brackets a sequence of channels; the one argument form suffices for single channels. |

| 5. | Finally, a lack of arguments suffices to share out an entire image buffer, such requires neither ranges nor coordinates. |

The following chart, illustrating the argument variants, employs this pipeline:

-input 150,150,1,3 -shared. < range & coordinates > -fill. {u(255)} -remove.

That is, we fill the shared buffer with noise; its appearance follows from how one of the argument variants delimited it:

| Arg cnt. | 150×150 img. | range & coords. | Description |

| 5 |  | 11,28,54,0,1 | pel resolution: x0[%],x1[%],y[%],z[%],c[%] - y, z, and c designate the particular image row, slice, and channel location to start counting pels. x0 designates a pel count from the beginning of row y; x1 indicates the location of the last pel. x0–x1+1 is the size of the buffer in pels. |

| 4 |  | 50,54,0,0 | row resolution: y0[%],y1[%],z[%],c[%] - z and c designate the particular slice and channel location to start counting rows. y0 designates a row count from the beginning of the slice z; y1 indicates the location of the last row. y1–y0+1 is the size of the buffer in rows. |

| 3 |  | 0,0,2 | slice resolution: z0[%],z1[%],c - c designates the particular channel location to start counting slices. z0 designates a slice count from the beginning of channel c. z1 indicates the location of the last slice. z1–z0+1 is the size of the buffer in slices. |

| 2 |  | 1,2 | channel resolution: c0[%],c1[%] - c0 designates a channel count from the beginning of the image buffer. c1 indicates the location of the last channel. c1–c0+1 is the size of the buffer in channels. |

| 1 |  | 1 | channel resolution: c0 - Shorthand for an image buffer consisting of one channel, counting from the beginning of the image buffer. |

| 0 |  | image resolution: (no args) Selects the entire image buffer. |

Range arguments are inclusive, so the pair x,x is legitmate and indicates that the buffer begins at x (so many pels, rows, slices or channels from the reference point) and consists of one unit: (x–x+1).

This command operates at a very low level and bypasses most safe guards and checks. That said, the shared command provides an extremely efficient, low-overhead mechanism to access image buffers. G'MIC sanity-checks ranges for buffer over runs, but deleting referenced images without doing the same on outstanding shares will probably trigger an operating system memory access violation, terminating G'MIC without giving it a chance to issue any illuminating mea culpas (even though it probably is your fault). Nonetheless, one shouldn't avoid the command for its fearfulness, never benefiting from its usefulness. If quantities stem from established image constants and the math is correct, the shared command furnishes the quickest means of accessing image data.

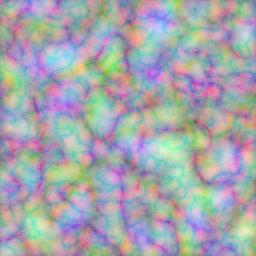

Discrete Turbulence Example

discreteturb: -skip ${1=32},${2=6},${3=3}

radius,octaves,alpha=${1-3}

-foreach {

-repeat s#-1

-shared. $>

-turbulence. {$radius*($>+1)},$octaves,$alpha

-normalize. 0,1

-pow. {1/3}

-normalize 0,255

-remove.

-done

}

$ gmic discreteturb.gmic 256,256,1,3 verbose + discreteturb. 120,7,1

[gmic]-0./ Start G'MIC interpreter.

[gmic]-0./ Input custom command file 'discreteturb.gmic' (1 new, total: 4596).

[gmic]-0./ Input black image at position 0 (1 image 256x256x1x3).

[gmic]-1./ Increment verbosity level (set to 2).

[gmic]-1./discreteturb/ Set variables 'radius=120', 'octaves=7' and 'alpha=1'.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Insert shared buffer from channel 0 of image [0].

[gmic]-1./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Render fractal noise or turbulence on image [1], with radius 120, octaves 7, damping per octave 1, difference 0 and mode 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize image [1] in range [0,1], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Compute image [1] to the power of 0.333333.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize images [0,1] in range [0,255], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Remove image [1] (1 image left).

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Insert shared buffer from channel 1 of image [0].

[gmic]-1./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Render fractal noise or turbulence on image [1], with radius 240, octaves 7, damping per octave 1, difference 0 and mode 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize image [1] in range [0,1], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Compute image [1] to the power of 0.333333.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize images [0,1] in range [0,255], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Remove image [1] (1 image left).

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Insert shared buffer from channel 2 of image [0].

[gmic]-1./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Render fractal noise or turbulence on image [1], with radius 360, octaves 7, damping per octave 1, difference 0 and mode 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize image [1] in range [0,1], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Compute image [1] to the power of 0.333333.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize images [0,1] in range [0,255], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Remove image [1] (1 image left).

[gmic]-1./ Display image [0] = '[unnamed]'.

[0] = '[unnamed]':

size = (256,256,1,3) [768 Kio of float32].

data = (121.628,133.139,144.106,154.303,163.74,172.078,178.802,184.268,188.645,191.372,192.188,191.191,(...),148.933,149.262,149.451,149.495,149.387,149.118,148.684,148.081,147.312,146.379,145.287,144.045).

min = 0, max = 255, mean = 169.415, std = 30.3728, coords_min = (252,184,0,0), coords_max = (130,13,0,0).

radius,octaves,alpha=${1-3}

-foreach {

-repeat s#-1

-shared. $>

-turbulence. {$radius*($>+1)},$octaves,$alpha

-normalize. 0,1

-pow. {1/3}

-normalize 0,255

-remove.

-done

}

$ gmic discreteturb.gmic 256,256,1,3 verbose + discreteturb. 120,7,1

[gmic]-0./ Start G'MIC interpreter.

[gmic]-0./ Input custom command file 'discreteturb.gmic' (1 new, total: 4596).

[gmic]-0./ Input black image at position 0 (1 image 256x256x1x3).

[gmic]-1./ Increment verbosity level (set to 2).

[gmic]-1./discreteturb/ Set variables 'radius=120', 'octaves=7' and 'alpha=1'.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Insert shared buffer from channel 0 of image [0].

[gmic]-1./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Render fractal noise or turbulence on image [1], with radius 120, octaves 7, damping per octave 1, difference 0 and mode 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize image [1] in range [0,1], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Compute image [1] to the power of 0.333333.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize images [0,1] in range [0,255], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Remove image [1] (1 image left).

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Insert shared buffer from channel 1 of image [0].

[gmic]-1./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Render fractal noise or turbulence on image [1], with radius 240, octaves 7, damping per octave 1, difference 0 and mode 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize image [1] in range [0,1], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Compute image [1] to the power of 0.333333.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize images [0,1] in range [0,255], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Remove image [1] (1 image left).

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Insert shared buffer from channel 2 of image [0].

[gmic]-1./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Render fractal noise or turbulence on image [1], with radius 360, octaves 7, damping per octave 1, difference 0 and mode 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize image [1] in range [0,1], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Compute image [1] to the power of 0.333333.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Normalize images [0,1] in range [0,255], with constant-case ratio 0.

[gmic]-2./discreteturb/*foreach/*repeat/ Remove image [1] (1 image left).

[gmic]-1./ Display image [0] = '[unnamed]'.

[0] = '[unnamed]':

size = (256,256,1,3) [768 Kio of float32].

data = (121.628,133.139,144.106,154.303,163.74,172.078,178.802,184.268,188.645,191.372,192.188,191.191,(...),148.933,149.262,149.451,149.495,149.387,149.118,148.684,148.081,147.312,146.379,145.287,144.045).

min = 0, max = 255, mean = 169.415, std = 30.3728, coords_min = (252,184,0,0), coords_max = (130,13,0,0).

Pastel Turbulence

The quotidian gambit finds one applying split to break out channels, then iterating over these as single-channel images, applying turbulence to each and adjusting arguments on each step to suit a fancy. With iterations concluded, one appends along the channel axis and moves on. Nothing wrong here; this workaday approach delivers the job on time and within budget. But the gambit may also leave one with a feeling of commissioned inefficiencies. And no wonder: a split along the channel axis ordains the creation of new images to contain the now-separated channels. With shared, one bypasses all that bit-shuffling. shared wraps a portion of the referent's image buffer, operating on that share furnishes direct access to the region of interest in the referent's image buffer.

In the wee hours, when one probably needs sleep, or in an especially labyrinthine script, the occasion of removing shared images from the stack momentarily jars: Did I just throw away a lot of work? (See discreteturb's repeat-done loop, last statement). May peace be with you. Deleting shares is simple housecleaning, perhaps to clear the pipeline for further sharing operations — though you can have multiple shares "open" on the same referent. Perhaps you wish to access disparate regions of the referent's image buffer. In any case, nothing is lost in such deletions because the reference still has the data — it has always had the data. The removal of the share causes no trouble. But if it is trouble that you want, then delete the reference image, leaving the shares with dangling pointers. Likely, the operating system will kill the G'MIC process — you may get a Killed message and nothing more. Bemused, in the wee hours and in the midsts of a labyrinthine script, you may wonder — with some emphasis — what is wrong with G'MIC now??? It will be clearer later in the morning — with the coming of daybreak.

Updated: June 3 2023 12:05 UTC Commit: 08aba74c6399524ca33910eb37838dafe1425f8a

Home

Home Download

Download News

News Mastodon

Mastodon Bluesky

Bluesky X

X Summary - 17 Years

Summary - 17 Years Summary - 16 Years

Summary - 16 Years Summary - 15 Years

Summary - 15 Years Summary - 13 Years

Summary - 13 Years Summary - 11 Years

Summary - 11 Years Summary - 10 Years

Summary - 10 Years Resources

Resources Technical Reference

Technical Reference Scripting Tutorial

Scripting Tutorial Video Tutorials

Video Tutorials Wiki Pages

Wiki Pages Image Gallery

Image Gallery Color Presets

Color Presets Using libgmic

Using libgmic G'MIC Online

G'MIC Online Community

Community Discussion Forum (Pixls.us)

Discussion Forum (Pixls.us) GimpChat

GimpChat IRC

IRC Report Issue

Report Issue